Why not bring in immigrants and refugees? These people just want a better life, why not open the doors and let them in?

Spandrell found a thread of a Belgian couple sharing their journey through the Congo in 2008, and it is interesting, and answers why we shouldn’t.

Big mistake. We were stuck. The water came to the bottom of the door. This particular mudpit had a bit of a funny smell. It was the favourite place of the pigs so it probably contained a fair amount of sh*t. It sure smelled like it. The entire village gathered round us while we got out, knee deep in sh*t.

They did not offer help.

We started clearing the wheels. Josephine hurt her foot on a stick, the pain could be seen on her face. The people thought this was extremely funny and burst out laughing. This was very humiliating for Josephine and I could see the anger on her face. We looked at eachother and understood that this was not the time to get angry or start discussions with 50 or so people. We continued to work. As I bend over to clear the mud from underneath the car my pants get wet up until my ehrm.. ‘privates’.. . Once again this is the funniest thing these people have ever seen. Hilarity ensues. This was very humiliating to us.

Eventually they offered to help us if we pay them. I tell them that I do not have money. They did not move an inch.

The same thing happens a little bit later:

No surprisingly nobody they offered their assistance, they even had some shovels. But they wanted money first. By now you probably think we are just stupidly stubborn and naive. We probably are, but we refused to give in to corruption. I once again told them they were free to help, but we would not give them money. So I continued to dig on my own with an entire village as an audience.

Here man meets tribal culture. He calls it corruption, but it isn’t, it’s culture. Why would people help others outside their tribe without a reason? Why would someone honestly expect unrelated others to help them?

I live in Canada. Everybody gets stuck in the snow on occasion. When you do, you’ll always have someone stop to help push your car out and get you on the way. One time I slid up the curb and got stuck in a small snowbank at 2 am on New Years (it was a patch of ice, not alcohol). The family in the house came out and helped me push and dig it out for 15 minutes, until someone in a 4×4 showed up and gave me a quick tow. I’ve stopped to help others push as well. Helping to jump-start someone else’s car is barely worth remarking on. It’s just something you do because you trust people will help you out when you need, and so we all get to avoid freezing to death trying to get our cars going.

This is a cultural practice built up by an uncountable number of positive interactions over a unnumbered years. The Canadian experience is the unnatural outlier, the Congolese experience is the natural norm. Helping strangers get their car unstuck is an unnatural cultural practice held by a limited number. It is just one of many western Europeans have built up. These practices have not built up in many (most?) other countries.

If you import foreigners from Congo who do not have this cultural practice, fewer positive interactions and more negative interactions build up, and eventually a some tipping point, you no longer have the cultural practice.

This is the harm immigration causes, it wears away at built-up cultural practices. The insidious danger of it is that this regression is barely noticeable until one day you get stuck, look around, and wonder, ‘why is nobody helping me?’

Of course, cultural practices go far beyond simply pushing someone’s car.

****

I asked them if they would want us to help them if they had a problem. The acknowledged this. I said what they would think if we asked for money before we would help them. They called us racists and immediately demanded money from us.

Welcome to your future.

Also, the demands for money or free stuff is omnipresent throughout the trip. Everywhere they go, someone is demanding money, drinks, phones, or the like from them. Is this the cultural practice you want imported to your country, where ‘le Blanc’ is seen primarily as a source of free stuff?

We opened a can of Coke (still from Zambia) and a jar of pickled onions to eat with our bread.

Those ‘horrible’ people did not have a Coke, even if they had the money to buy it, it was not avaialble. They did not have pickled onions either. And between the two of us we ate as much bread as an entire family would eat for an entire day.

We tried putting things into perspective. Maybe we shouldn’t be here after all?

This is what immediately follows their ‘stuck in a mudpit’ story. The answer to the question is ‘correct, they don’t belong there’.

But more interesting is how they do not seem to make a connection. Maybe there’s an underlying reason why people who won’t help others stuck in mud don’t have Coke and pickled onions available. Coke and pickled onions require cooperation in the marketplace, but how can there be cooperation when you can’t even trust your neighbour to help pull you out of the mud?

****

If you want to know why there’s no social trust, here’s an illustrative example:

We came across a small motorcycle. You’d see them from time to time, it is the most luxurious transportation people have here. They are litte chinese 50cc (or 125cc) bikes. We stopped to let him pass and he stopped to greet and ask us if we had some oil for his engine.

All over the world there is an unwritten rule that in remote or difficult to travel areas people help eachother. That is why in the sahara everybody says hi to eachother. That is why in the Mongolian steppe people drive for kilometers just to check up on you. People help when needed as they know they will be helped when they are in need. We very much honour this unwritten rule and will always assist when we can.

So when this guy asks for oil, I do not hesitate and take out a my spare can of oil. I warn him that this is oil for diesel engines, but that does not matter to him. It is probably the best oil he would ever find to put in his little bike. As I am pouring oil from my can in his can the passenger of the bike starts begging with Josephine. I am not impressed when Josephine tells me. And when the bike owner too start to ask for money, it really pisses me off. We are helping this guy and still he begs for more? So I pour the oil out of his can back into mine and tell them to sod off. In our car and off we go.

For almost a month now we were in a serious fight with Congo. We were fighting against corruption. We were fighting against the roads. A constant battle. Congo was giving us a serious beating, but we stood strong and did not give in. Slowly but steadily we were winning this battle against the Congo.

But while we were so busy battling the roads and the corruption, Congo sneaked in from behind. It had transformed us into loud and angry people. With no remorse, no compassion, and a total lack of rules.

What happened to the unwritte rule of the road less travelled? The rule we nohour so much? All out of the door..

Congo had beaten us a long time ago already. Just like it had beaten most of its own citizens.. And we didn’t have a clue

The defections finally got to our generous tourist and finally defected himself. I wonder if this will cause him to further defect in the future?

Foreign cultural practices are acidic and burn away your cultural practices.

****

Here’s the price for not having a culture of trust and cooperation which would allow for road-building:

As said, traffic is always local. They somehow manage to get cars into larger towns and then drive it around town, but no trough traffic. So cities/towns/village that are not on a river or on the limited railroad network have very limited supplies.

Up to 600kg of goods are transported on these bicycles. They do not ‘ride’ them, but push them instead. You can see there is a stick connected to the bikes handlebars.

This is the major transport method in Congo. It is probably one of the most ‘popular’ (this does not seem like a good wordchoice) jobs. There are fixed routes and people often travel in groups. For security reasons but also to help eachother on the hills.

At regular intervals on the main “bicycle” tracks there are “service stations”. This is usualy a small hut where one can eat a meal of fufu. They would also have a pump and some basic tools to fix flats.

We saw many of these overloaded bicycles before, but on this stretch of the road it seems to be the only means of transportation.

It must be very hard work to get these loads over the sometimes very rough roads. The ‘drivers’ are away from home for weeks on end and probably barely make any money out of it.

And here’s another cost:

We came across a truck that was parked in the middle of the track. Luckily the surrounding area was pretty open, so we could pass it.

Us: “Bonjour, ca va?” – “Hi, how are you?”

– Them: “Ca va un peu bien ” – “I am doing a little bit ok” -> typical Congelese answer this!

Us: “Votre vehicle est en panne?” – “Did you truck broke down?”

– Them: “Oui, mais ils vient avec des nouveaux pièces” – “Yes, but they are coming with spare parts”

So we chat a bit and we ask what their problem exactly was. They left Ilebo for Kananga with a load of building materials for a rich guy in Kananga. Their engine had completely seized. Their cargo was transferred onto another truck and they had taken the engine out and transported the engine to Kinshasa to get it rebuild. In the meantime the truck ‘crew’ stayed onsite to safeguard the truck. But they were very happy as they just received news that the necessary parts for the engine were now ordered in Germany, so the parts would come arrive in Kinshasa in a few weeks time!

A fascinating story, and they told it as if the was the most normal thing in the world. Fair enough. We said our goodbyes and asked them one more final question. How long had they been here?

“Un peu plus qu’un an maintenant” – “Just over a year”

“The most normal thing in the world“. Is this the culture you want to import?

****

After the preceding stories, someone did help them:

It took three more attempts to drive out before the village priest (7th day Adventist by the way) encouraged a few strong men to help.

***

Some other people in the Congo were more proactive:

When we continued on the same road we would pass other smaller mudpits. These bogholes always had a “crew”. When a truck arrived, they would throw in rocks so the truck could pass… for a fee ofcourse. After the truck passed they removed the rocks again. A lucrative occupation!

In our books this is just plain wrong and we refuse to support such behaviour. So we always charged trough in 4×4, hoping we would not get ourself stuck.

The corruption is omnipresent and not just limited to roads. The tourists can hardly go anywhere without some official or another demanding a road toll, a non-existent “tax”, or a “fine” for some made-up infraction. As the tourists note, despite all the road tolls:

Nothing ever returns to the maintenance of these roads, or anything remotely related to the province it is in. It shows:

All the roads are like that or worse, My favourite is the one with the tree in the middle of it:

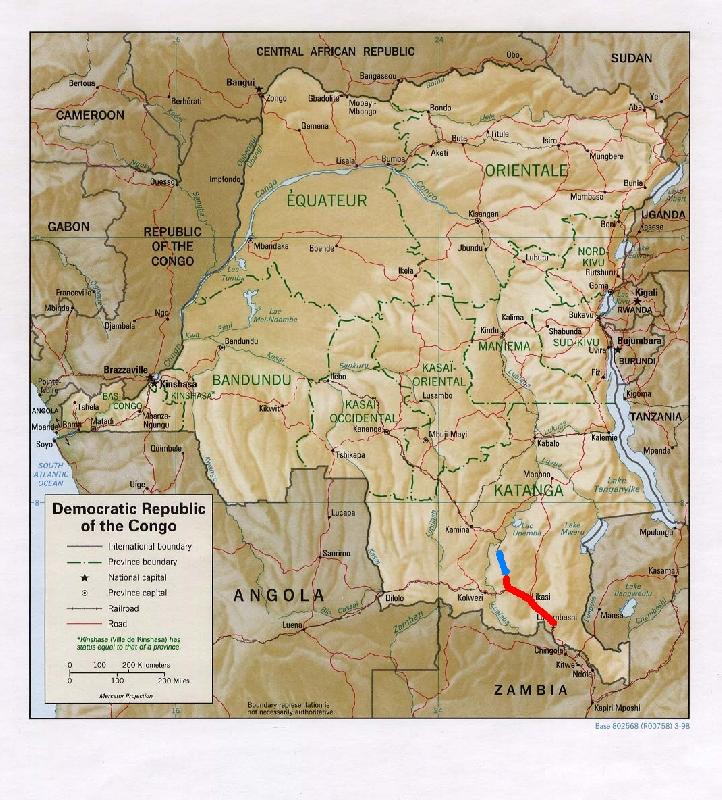

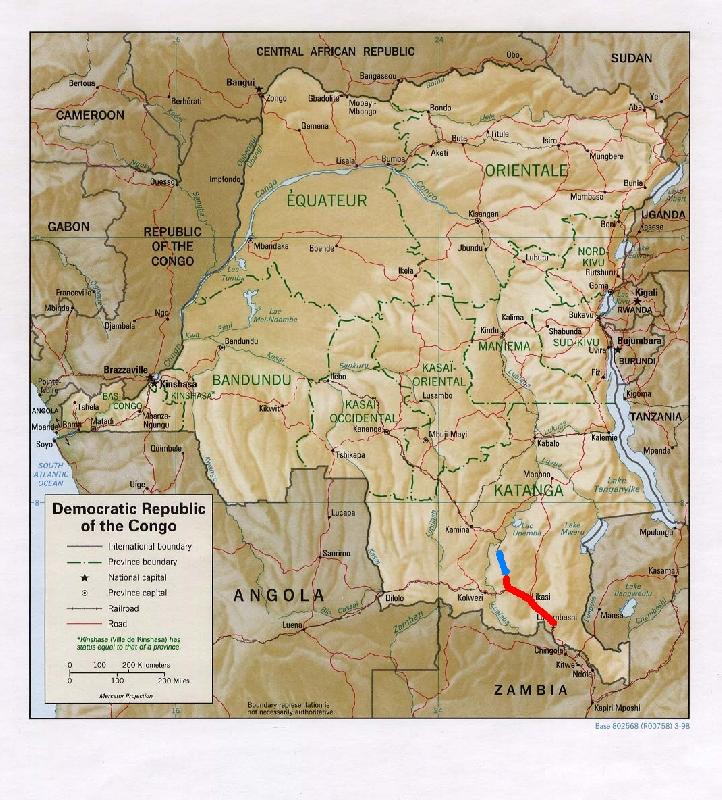

Here’s there first two days of travel. Remember, day one was the fast part of their trip with the best roads.

Less than 200 miles in day one, barely 50 in day two, while driving a sturdy 4×4. That’s how bad the roads are.

But between the corruption and and distrust, why would anyone build a decent road? Who would build a decent road?

There was one group who tried, the Belgians, which brings me to the next point.

****

At some points the trip reminds me of Skyrim. The Congo resembles a pre-civilized society but there’s the (sometimes functioning) ruins of an ancient civilization scattered about.

Fallout 4 or a Belgian Ruin in the Congo

They’re driving down unkempt, potholed dirt roads, then suddenly:

The bridges were something we were very concerned about upfront. Congo has a lot streams and rivers and we knew the roads had not seen maintenance in many many years. If a bridge broke down, that could be a major problems. Up until now however we did not have any problems with the bridges. Some of the smaller bridges might have been dodgy, but all of them were passable. Most of the large bridges were fortunately made out of steel and in reasonably good nick.

Take the bridge we just crossed for example. I find it amazing that is still there. Numerous armies have crossed the Congo in the last 20 years, chasing their enemies down to the capital. Now, I am not a military expert, but if my army was losing terrain to the enemy army and I have to retreat. The one thing I would certainly do was blow up all bridges after me. Had it happened but was the damage so small that it could easily be repaired? Or did they just not bother? Or did they lack the explosives and time to actually blow it up? Who knows…. but at least the outcome is good for us now!

A bridge made by the evil Belgian colonialists over a half-a-century ago still functions, but the Congolese can’t keep basic roads functional. Here’s the ruins of “what once must have been a grand building… marked with logos from a Belgian University… [that] must have once been some scientific study centre of sorts.”

Everybody talks shit about imperialism and colonialism, but when the Belgians were there the people of the Congo had peace, order, bridges, working roads, a functional bureaucracy, non-corrupt police, and scientific study centres. Are the Congolese better off being ‘free’?

Here’s the tourist on the dark Belgian history:

I presume you are referring to the “not so nice” role Belgium has had in the history of Congo. For a while I thought that would be a problem as well, but it isn’t. Just about anything that still exists in Congo is made by the Belgians. The older generation who had their education from the Belgians really have fond memories of that era. And at the moment Belgium is still one of the main funders of the country (via aid). The dark pages of history during the Leopold 2 era is not what the Congolese people think about. All in all I think being Belgian was actually a plus. As a matter of fact, a lot of people asked how things were going with the “war” in Belgium :-o

****

Speaking of functional bureaucracy, mismanagement is not limited to infrastructure. Here’s the tourists on getting a permit to be tourists:

Nobody really know what kind of permit one needs, let alone where to apply for it. But everybody agrees that a permit is required. Officially it has got something to do with the many mining areas to be crossed. We contacted the few people who have attempted travelling trough congo but they too never managed to get hold of the permit. One of these guys did get arrested and deported because he could not provide a permit.

Our Belgian Consulate really tried hard to get this stupid little piece of paper for us, but to no avail. They even managed to get us invited with the governer of Katanga, but he too could not give it to us. After many days of trying we asked the consulate to give us some sort of official looking letter with an official looking stamp. We would chance it without the permit!

****

There are some actual functional paved roads around, made by foreigners:

So, why is there an asphalt road in the middle of Congo? Not connected to the rest of the road system (due to lack of road system).

There reason is simple: Diamonds. This is the main diamond center of Congo. This has attracted many people ofcourse, but the local people barely benefit of the natural wealth of the region. Officially it is the third largest city of Congo, after Kinshasa & Lubumbashi. Although by now it is probably the second largest city with over 2 million inhabitants. It also a politically important region. Most of the recent political problems start here. When Mbuji-Mayi “explodes” the rest of the country usually follows shortly after.

The diamong mining companies ofcourse need transport. Most is done via air, but the heavy supplies (fuel) are brought in by train. The nearest train station is in Mwene-Ditu. Hence the tar road between Mwene-Ditu and Mbuji-Mayi.

It’s hard to say “the local people barely benefit” when the mine is the only reason there’s a decent road in the area.

Here’s an interesting tidbit on who they talked to while prepping for their trip:

2) Coca-cola company: If there is ony thing you can find anywhere in the world it is Coca-Cola. They should know how to get their goods in the country. We had no response on mails, so we called them up. Their answer was pretty short: They do not have a distribution network outside the major cities in Congo 8O And it proved to be true, Congo is the first country we have visited were Coca-cola is hard to get once you leave the major cities.

****

An interesting thing about the trip, is the number of Catholic missions in the Congo, how often that’s where the tourists stay at them, how much the tourists appreciate them and their kindness, and how much a relief the priests are. From the way the tourists talk about them, Catholic monks seem to be what keeps the country even somewhat functional. I’m not going to quote all of the references, but here’s a few.

Here’s some priests picking up the white man’s burden. It speaks for itself:

The priests (Brothers actually) are nice guys. There are 4 of them, young and smart. All of them have studied in Lubumbashi or Kinshasa. After they finished the seminary they were sent to a mission. They cannot choose which one. We could hear the sadness in their voices when they told their stories.

They sampled the “world” when studying, they have a degree (one of them had a masters in engineering) and then they are sent to a mission. They know they will probably never have the chance again to live in a city. At the mission they take care of the kids, teach, etc.. A noble and rewarding job. But they carry all this knowledge that they cannot put in practice here. They have no computers, no tools, no electricity, no budget, …

Their living quarters were very comfy and clean for Congolese standards. They had a radio and a TV set. Because of their proximity to Lubumbashi they had a regular supply of newspapers.

The priest-engineer was setting up a project to generate clean energy from a river. He had a recycling project. A radio project. An irrigation project, … He had to run all these projects without any funds, without material. So many ideas, so little chances.

They remained positive but you could see it in their eyes that they were sad. Without a doubt they would take the first opportunity to get out of there. It would be a great loss for the mission and the village but I couldn’t blame them. In the way our talks went we thought we could hear them crying for help. To take them to Europe, to give them funds, to supply them with material. They did not speak these words, but to us it was clear that they really longed for those things. We were not able to provide this. It made us sad and we felt guilty.

Here’s another set of priests carrying the burden and the thanks they get for it:

We rolled into Kamina and had a warm welcome by several “frères” (Brothers), among them Frère Louis, the belgian brother that hosted us in Luena. The other frères were Croatian. They all have their missions deep in the brousse, but this week they had their annual gettogether.

The missions was big and well organized. They had all the facilities, even a workshop. They were responsible for almost everything functional in Kamina. Churches, school, farms, factories, …

…

That night we talked for hours with Frère Louis. Our little adventures here dissapear in the nothing compared to everything he went trough. He had been in DRC for over 40 years, he stayed during all the wars. He had to abandon everything and run for his live three times as teams were sent out to kill him. But he always returned. Many books could be filled with his adventures.

He is also responsible for most of the bridges Katanga. He build hundreds of bridges himself. He has a small working budget from Franciscans, but he funds most of it all by himself. He has put every last penny in the Congolese people. That is why his house in Luena was so rundown.

He also told us about the Mayi-Mayi rebels that still roam the jungle. We were not prepared for the horror stories we would hear. I still have problems giving these stories a place. They are not just stories though, he gave us a 100 page document with his interviews of victims. If you thought, like us, that cannibalism was something that belonged in comic books and dusty museums about Africa. You are wrong. :cry:

But not everybody is called to the self-sacrifice of the mission field:

Unfortunately the father of this mission was not there, but his apprentice was. A very young guy, fresh out of school. He was not happy to be here, that much was clear. He did nothing else but complain and he would whine on endlessly. He was not a bad guy, but was wan’t very good company either.. oh well.

And not every priest remains uncorrupted:

We discussed our plans with Abbé Omer in the garden of the mission (it must have been a wonderfull garden back in the days.. now it looked a bit rundown). The good news was that there was good ferry here that could take us across the mighty Kasai river. The bad news was that nobody every uses that ferry and it does not see any regular action.

Omer knew the guy who was responsible for the Ferry, a chap called Barthélémy. He even has his phone number, but he does not have credit on his phone. No problem, he can use ours. A conversation in Lingala starts, it takes about ten minutes until we run out of credit on our phone. I actually think they talked 1 minute about the ferry and the other 9 minutes about other things, but anyway. Here was the deal:

– Price for a two-way trip is 50$US

But,

– we have to supply our own diesel the engine of the boat. 150 liters is required (!). that’s about 200$US (Diesel here is cheaper because they have a regular supply via boats from Kinshasa).

– we have to supply two batteries to start the engines of the boat

– the ferry is on the other side of the river and they would only be able to get it across somewhere next week

That’s just great!

We immediatelly uttered to Omer that that was a ridiculously high price, one we would never pay. And that we wanted to cross as soon as possible. preferably tomorrow.

What followed was a very difficult negotiation. Abbé Omer insisted that he acted as an intermediate person. According to him to protect us from getting ripped off (because we were white). I was actually convinced that he was playing a game with his mate Barthélémy to make some money out of us. It took us many hours on the phone to finally convince this Barthélémy to come to see us to discuss the price. He would come at 8 the next morning.

Later that evening Omer suggested that we he would have to inform the police of our presence (c’est normal!), it took us a lot of persuading for him not to ‘give us in’.

Interesting that Omer is a local.

****

Of course, some secular non-profits are there to, but they are not as effective as the evil Catholics, MNC’s, and imperialists:

They told us about the mysterious roads. Apparently some NGO (they did not know the details… or they told the details and we forgot) has funded the construction. Several teams started working at several locations. The different bits were supposed to connect at one point. As of recent, work had nearly stopped… no more budget. It was unclear if more budget would become available or not. In any case the idea of the construction was to invest all the money in labour instead of buying an expensive CAT. Great idea ofcourse, that way all the money stayed in DRC, instead of filling the pocket of some bigwig at CAT. If you look at the road it was quite a feat. They thought about drainage and everything. Unfortunately they could not compress the earth enough with the tools they had. We already started a few ruts, it would only take 1 heavy truck to completely destroy these roads again. These roads would not last a rainy season.

Here’s Barthélémy’s ferry:

We couldn’t believe our eyes when we finally saw the ferry.

It looked brand new!

It wasn’t..

A German (?) NGO had funded the restoration of the ferry recently. It had received a nice fresh coat of paint, but the money to rebuild the engines had gone missing.

****

Here’s some more local cultural practices excerpted from a 131-page document by a priest:

“Y”‘s brother went fishing in Missa and saw mischief like cutting of ears. They fry the ears in a pan eat them. They make the victims look at how their own ears are being fried and eaten. They are being accused of cooperation with the Congolese FAC army. The May May continue to eat humans. Y’s brother managed to escape to Bukama, this is where I met him.

…

They kill those four soldiers and eat them. They then carry one of the heads of the murdered soldiers to Kintobongo and put the head on the table in our mission. They do this as warning not to attack hem, if not this is what happens.

…

..The hunters (May-May) asked food at the woman of Chef Kitumba. The women told they did not have food. The hunters then demanded that they roast their children for them to eat.

…

The commander Bati dared to display a naked woman. With a pen he pointed at every part of the “intimate organs” and told the onlookers the names in dialect. What a humiliation.

…

We are living in a situation of pure and simple cannibalism. The may-may plunder, rape and kill the civilian population. They then eath their meat, raw or smoked. This is true for the May-MAy chief Kabale, who was killed recently (15/05/2006) by the population of Kayumba.

Do we really want to bring these kinds of cultural practices here?

****

Of course, it’s not all bad:

We stopped in the first village. A car in the village.. with white people in it. Now that is an attraction ofcourse. And if they are covered in mud from head to toe it is even more interesting.

I do not have to explain we drew a bit of a crowd?

But people were actually quite nice. They offered us to use their shower (a tree with a mud wall before it and a bucket) and after an hour or so they actually left us alone.

Later that evening some kind of custom officer came to see us. He wanted to see our permits and whatnot. We kindly told him to bugger off and come back tomorrow. Surprisingly, it worked. Next day we were gone before he came back ;-)

As soon as it got dark we got into our tent and looked outside. We could see several fires in the village were people would gather around and sing and dance (mostly women). Small groups of men were having discussions. Peaceful village.

But small villages aren’t all good either:

The first village we encountered seemed deserted at first, but as soon as we entered the village we saw people coming at us from all sides. They had machetes and sticks and were shouting. “Des Blancs. Argent!” – “White people. Money!”. They were all over the place. This was not good! I floored it and sped out of the village. A rock hit the back of our car.

What in gods name was that all about?

Very few Congolese had made us feel welcome, but this was plain agression! It scared the hell out of us.

We passed another village, and once again a mob formed as soon as they heard us coming. Machetes flying round, racist slogans shanted. Once again we did not give them the chance to get near us and blasted out of the village. They tried following us. This was turning ugly, if we would get stuck here we would be in big trouble, these people did not want a chat!

****

Anyway, I’m about twenty pages into the thread and it goes on for almost 100 pages. I’m done reading and commenting on this (for now?), but I hope you found this illuminating, or perhaps endarkening?