I wrote this a few months back, but never got around to posting it. Scott’s post on wage stagnation reminded me to post it, because I discuss some of the same things here, while he ignored what I think is the most obvious cause of wage stagnation.

Someone posted on twitter, asking why kids became expensive. I answered mostly about the spiritual reasons: the unwillingness to sacrifice. And that’s true; kids are affordable, IF you’re willing to make the necessary sacrifices.

However, as Nick B Steves has said, ordinary virtue should not require heroic effort. You can have many kids if you’re willing to make extraordinary effort to do so, but any sane and healthy society should make it relatively easy to have many kids, ours does not. So,I’m going to show why kids are so expensive.

****

Wages

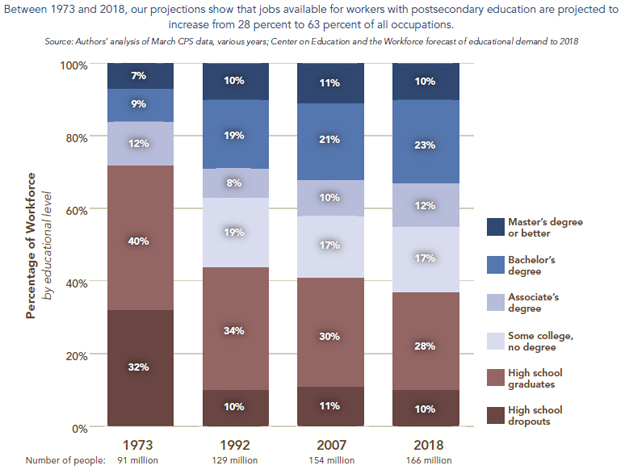

The first reason is wages. Inflation-wise wages have been stagnant since about the 70s. Despite massive increases in productivity, people are not making more real money.

Wages are determined by where the demand for labour and the supply of labour meet: how many jobs are there and how many people need jobs. This is elementary economics, but I’m going to make it clear here, because when it comes to discussing labour supply and demand, I notice people tend to make self-serving analyses as if basic economic principles change when it comes to labour, so I want to make it clear:

The more jobs that need to be filled, the higher the demand for labour, so this pushes wages up. If the jobs to be filled decreases, demand for labour decreases, which pushes wages down. If the size of the labour force increases, labour supply increases, which pushes wages down. If the size of the labour force decreases, labour supply decreases, pushing wages up.

Over the past 60 years or so, there have been multiple major trends both increasing the labour supply and decreasing labour demand.

The biggest trend is feminism. Feminism pushed women into the workforce which (more or less) doubled the labour force over a period a few decades. This pushed wages down hard.

The second major trend is immigration. Since the Immigration and Nationality Act was passed in 1965, opening immigration up, 59 million immigrants (as of 2015) have arrived in the US. The US population in 1965 was 194 million, in 2015, it was 321 million, for a total growth of 127 million. 46% of US population growth since 1965 has been from immigration.

That is a unnaturally massive growth in the labour supply, which has had a massive downward pressure on wages.

I will note here, that keeping wages low has been a near explicit part of the arguments for immigration. “Labour shortage” is synonymous with “wage shortage”; when employers argue that there are not enough workers, what is really being said, is they are not paying enough to attract workers. “Jobs Americans won’t do” is synonymous with “Jobs Americans won’t do unless paid more than currently offered”.

To make matters worse, the 1965 INA opened up immigration from third world countries, where wages were already naturally low. So labourers being imported into America would be willing to work for much below what an American would accept as reasonable, increasing the downward pressure on wages.

While these two trends where increasing labour supply, other trends were decreasing labour demand. Particularly off-shoring and mechanization.

Off-shoring moved industry from high-wage America to low-wage third-world countries, while mechanization has replaced human workers with machines. Both of these have had large depressive effects on labour demand, and therefore wages, particularly in non-service, low-skill occupations, which are the easiest jobs to both automate and move.

You can’t afford children, because you’re not getting paid decent wages because capital has systematically forced you into competition with poor third-world labour, imported labour, and your wife over jobs, forcing wages down.

****

Housing Costs

Housing costs are the single biggest expense (rivaled only by taxes) to your average person, and housing costs have exploded.

In 1960, the median house price was $58,000 (in 2000$). In 2000, the median house price was $119,600. In 2015, the median house price was $294,200 (in 2015$), which comes to $213,700 in 2000$.

In 55 years, housing prices have almost quadrupled, while wages have stagnated.

One of the major reasons is the increase in housing size. Since 1975, housing size has doubled. But that does not explain a quadrupling in housing costs. It would at best explain a doubling, but should be less than doubling because new marginal square footage should theoretically be cheaper due to the fixed costs in a home.

Another major drivers of house pricing includes increased demand from the fracturing of the family. In an intact nuclear family, two parents and their children share 1 house (possibly with a grandparent or two). In a divorced family, two parents and their children share 2 houses. An unmarried man and an unmarried woman have 2 houses (roommates amerloriate this to an extent). A single mother with children and her baby daddy have 2 houses. Etc. Throw on top of this the shift from multi-generational homes, and the fracturing of the family and the turn away from marraige has had a large, but, AFAIK, unmeasured effect on home prices (this would make a good study proposal for any economists out there).

Another major driver is immigration. 59 million people needing housing is a huge upward driver of housing demand and therefore housing prices.

A third major driver is schooling and safety. “Good schools” is a major driver of house prices and “safe neighbourhoods” because most parents, understandably, want their kids to get a good education and to be able to live without worry they’ll won’t become involved with or victims of drugs, gangs, and crime. Everybody is also aware that “good schools” and “safe neighbourhoods” are politically-correct codes words for schools and neighbourhoods without poor minorities who statistically make schools bad and neighbourhoods unsafe.

Because federal laws make discrimination in housing on any basis but price illegal, the only way to keep schools good and neighbourhoods safe is to discriminate on price. This puts a huge upward pressure on price, as people move to high price neighbourhoods to escape poor minorities (who may then follow them, because they too want good schools and safe neighbourhoods, forcing the process to repeat, escalating prices even higher).

Because of this, safe, affordable housing is functionally illegal in American cities and prices ever increase.

****

Two Income Trap and Child Care

The increased upward pressure on housing prices has the side effect of forcing more families into the two income trap, so they can afford a good house.

This has a variety of effects that increase costs, making children expensive.

Child care is the largest of these. As I’ve explained before, affordable child care is impossible, so child care will immediately eat up a significant portion the second income. Child care by itself, is a major factor of why children are so expensive.

A second income usually requires a second vehicle (more on this below), another major fixed expense. A stay-at-home parent has time to cook home made meals, mends clothes, and participate in other cost-saving activities; a dual income household will eat out more often, purchase more expensive pre-made food, have to replace clothes, etc.

The two income trap imposes a number of large extra costs on families and removes many cost-savings that an at-home parent allows.

****

Taxes

I was going to write about the increasing tax burden here, but I couldn’t find much much data on the overall US tax burden; most of it was just federal tax rates, and calculating overall tax burden for the average middle class person over time is much more effort than I’m willing to put in to a blog post.

But according to this 2012 NYT article, the overall tax burden has been declining somewhat, except for low-income people, who continue to pay minimal taxes.

So we’ll say increasing taxes probably aren’t particularly responsible for kids costing too much.

****

Vehicles

Among average people, vehicles are second largest major fixed expense after housing, and they have generally gotten more expensive over time, primarily as more families have moved to being two car households and gas has gotten more expensive.

This site compared a few classic cars and all have increased by half to almost doubling since 1965 (inflation-adjusted). But these are classics and so might no be applicable.

According to Wiki, the Chevrolet Impalla was the best-selling full-size car in 1965 and is still the best-selling today, so we’ll use this and assume other similar cars are competitively priced. In 1965, a 4-door V-8 sedan Impala was 2,779, which comes to $20,910.17 in 2015$. The base price of a new Impala in 2015 was $27,700. An increase of about a third.

But large families need more than five seats. The 1965 Impala 9-passenger station wagon was $3,073, $23,122.33 in 2015$, the 6-passenger was $22,347.32. You generally can’t buy station wagons today, because US regulations classified them as cars, making them uneconomic to produce under US fuel standards, which was a major regulatory backfire for environmentalists, as families switched to minivans and SUVs, which were much worse on fuel. The best-selling SUV in 2015 was the Ford Escape, which started at $24,000, but only can seat 5 passenger. The best-selling minivan, is the Dodge Grand Caravan, it seats 7 passengers, and started at $22,000. The Chevy Express was the cheapest 9+-passenger I found on a site, and it starts at $29,000 for the cargo version, so probably just a bit more for a passenger vehicle.

So, it looks like 3-4 child family vehicles are significantly more expensive to buy, as are larger 8+ child family vehicles, but, contrary to my expectations, the large 5-7 child families are about the same.

Except that the SUV’s and vans cost a lot more in fuel and as mentioned above, 2-income families now almost always need 2 vehicles.

Gasoline costs have increased: with the exception of the 1973 and 1979 oil crises (when prices hit $3/gallon, post-WW2 gas prices generally stayed between $1.50-$2/gallon (in 2015$). Since 2000, gas prices have ranged between $2.50-$3.80 per gallon. Since 2006, gas prices have generally been higher than the $3/gallon they were at the peak of the oil crises. During this time gasoline usage has also been increasing, likely largely due to increasing suburbanization.

Another hidden cost: older vehicles were generally easier to repair and maintain at home, but the increased inclusion of electronics in vehicles, makes it increasingly difficult to repair without very expensive specialized electronic equipment, necessitating an increasing reliance on professionals for maintenance and repair, adding significant cost.

So, the need for two vehicles due to the two income trap has increased the cost of vehicles significantly for your average family, while vehicles themselves have become moderately more expensive. The cost of gasoline has increased significantly while consumption has increased.

****

Food

Food is generally the fourth biggest cost to families after housing, taxes, and vehicles. The average American spends less on food, as a percentage of income, then they used to. Hoever, good expenditures have stopped declining and been flat over the last 15-20 years.

However, this is deceptive, if you look at average household size since 1960, it mirrors average household size relatively closely. The levelling off of food costs as income share matches the levelling off of household size. This suggests food costs have been mostly constant per person, but less kids means less spending on food.

In a time of major productivity gains and stagnant wages, food costs have not really shrunk.

A major cause of this is the increase in eating out. It costs more to eat pre-made food than it does to make your own food. The average American now spends about 43% of their food budget on eating out. As well, when eating in, they are more likely to buy expensive pre-made meals than making their own. All this increases food bills.

The primary cause of this increase in eating out and in eating pre-made foods, is the two-income trap. When one parent was at home, they had sufficient time and energy to create homemade food, saving money. When both parents work, food preparation time becomes a luxury often foregone due to a lack of time and motivation.

In addition, to eating out costing more, eating out itself has increased in cost.

In economics, there’s an informal purchasing power parity index known as the Big Mac Index, that can roughly how close inflation rates measure actualy close consumer price data.

In 1968, when it first came out, a Big Mac cost $0.49, $3.34 in 2015$. In 1986, the first year of the Big Mac Index, it cost $1.60, $3.46 in 2015$. In 2000, $2.51, or $3.45 in 2015$. In 2015, the most recent year the BMI measured, it cost $4.79.

The cost of a Big Mac stayed relatively even until sometime after 2000. Since then there has been a ~40% increase in the cost of a Big Mac beyond inflation. My anecdotal experience in Canada and basic market competitiveness theory, suggests that this growth is probably true across eating out on average.

So eating out, which is 40% of your food bill, is now 40% more expensive than it used to be.

I’ll also note here, that the rapid growth of Big Mac costs past inflation, suggests that inflation has been severely underestimated, in which case, everything I’ve posted is much worse than the numbers suggest. I’ve always been skeptical of CPI, but a 40% extra increase over 15 years in something as basic and omnipresent as a Big Mac heightens my doubts.

Food costs haven’t really increased, but they haven’t particularly decreased either.

****

Education

Saving for college is a major expense for many middle-class families. Lots of ink has already been spilled over this, so I’m not going to repeat much. College has been increasing in price much faster than wages. 8 times as much according to this article.

A lot of young people start off with a lot of college debt. The average student loan borrower has $37k in debt upon graduation. That’s a lot of money, the equivalent of a down payment on a house. Instead of buying a house and accumulating capital, they’re paying off usury.

And they’re not really getting anything of increased value for this debt. The money is being burned in cost disease and their job prospects are worse than those of college grads decades ago.

****

Consumer Debt

Now, one of the major destroyers of people is usury. The average millennial has $42,000 in debt, the plurality of which is credit card debt. The average American is $33,000 in debt. I’ve already written about usury (and inflation) before, but debt and debt payments are major

Usury takes advantage of the average person who is not mentally equipped to fully understand the implications of debt and compounding interest. It shackles them in debt bondage. The average American spends $280k over their lifetime just on interest. The average person with credit card debt pays $1.1k in interest each year.

Household debt has increase from 31% of income in 1951 to about 100% now (it was up to 120% during the housing boom). All this debt means increased interest payments to banks.

Usury is strangling the average household, particularly the young.

****

Communication Technology

This is a simple one, but the average American user spends $47/month on mobile phones and $132 on cable and internet. That’s almost ~$180/month. When I was growing up, cable was rare and internet and mobiles practically non-existent. And this is just monthly bills, not including the purchase of HD TV’s mobile phones, and computers. This is a huge added expense most families take on.

****

Personal Choice

Finally, personal choice is why you can’t afford children. This is what my tweets harped on. People can’t afford children, because they are unwilling to sacrifice for them.

People eat out instead of making meals at home (driven by the two-income trap). People buy larger houses than they should (driven by “safe schools” and the two-income trap). People by two cars (driven by the two-income trap) and new cars. People go into consumer debt. People take useless degrees. People buy luxuries.

There are major structural issues making children expensive, which I’ve outlined above, but on the individual level, you can probably afford children if you are willing to sacrifice. People have been raised and become accustomed to luxuries they can’t afford (hence the massive amount of consumer debt most have). This may be due to structural issues, but on an individual level you can probably afford kids if you sacrifice.

Don’t go into debt for a useless degree; take trades or get a useful degree. If one of the parents stays home and engages in traditional money-saving practices (such as home-cooking and coupon-clipping), the family can avoid buying a second vehicle and paying child care costs. This will require buying a smaller house, children may have to share rooms and you may have minimal private space. Luxuries in entertainment and food may need be cut back. Cable cut. Home internet forgone for mobile only, or vice versa. It may require moving to a lower cost county or state.

Your grandparents raised 6 kids in a small 3-bedroom house with no TV, 1 car, minimal entertainment or luxuries, home-cooked meals, and penny-pinching. You can too if you will it enough and are willing to sacrifice for it.

****

The reason you can’t afford children is because wages stagnated while costs increased across the board.

Wages have been destroyed by a rapidly expanding labour pool due to immigration and feminism. At the same time, housing costs skyrocketed due to the two-income trap, a quest for safe schools and neighbourhoods, rapidly and artificially expanding population, and family breakdown. The two-income trap necessitated two vehicles, which along with gas greatly increased transportation costs.

Education has trapped the young in debt, while general usury eats people alive and prevents them from accumulating capital.

Finally, you’ve been raised to be accommodated to a lifestyle and luxuries you can’t afford and which you finance with debt.

On a personal level, you can overcome this and have children by making major sacrifices. On a societal level, it is insane and unhealthy to require the average person to make inordinate sacrifices just to be able to afford children. Any decent and sane society will do what it can to make raising a family comfortably affordable to most people.

Our society has been designed to destroy your ability to have children without either being rich or taking on massive usurious debt and making inordinate sacrifices.

****

Post-Script: I am not blaming immigrants for immigration, minorities for integration, or women for feminism. All of these are structural issues basically forced upon an unwilling populace by government and capital. Immigrants, minorities, and women followed, as would be expected, the incentives given them, and I generally don’t fault people for following incentives unless it’s a heinous evil, which none of the individual actions taken under this incentive structure would be. In fact, minorities and women probably suffered the most under this regime. Immigrants generally benefited, but being foreigners had minimal hand in the original changes in the 1960s.

The ones at fault are government and capital who imposed a destructive economic incentive structure upon society so they could destroy wages and increase consumption to feed their greed and lust for power. They are the ones who caused this and the ones responsible for why you can’t afford children.

Make sure you aim the blame properly.