Scott Alexander examines technological unemployment, concluding that there it is unlikely there is technological unemployment.

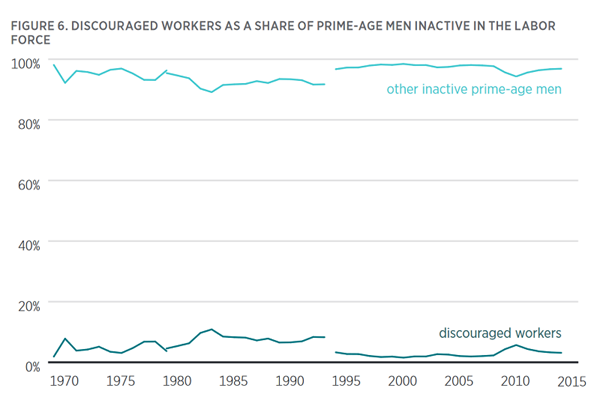

He notes that the number of prime age male labor force non-participators (PAMLFNPers) is increasing. He looks at this graph, and states it is not discouraged workers who are not in the labour force:

Concluding this section Scott states:

Second, Winship’s optimistic take on PAMLFPR is hard to easily refute. PAMLFNPers pretty clearly say they’re not looking for jobs, and they’re just perfectly innocuous students, retirees, etc. We have trouble believing them, especially based on their demographics. But it’s very hard to look at the increase and see a place where unemployment issues could have slipped in.

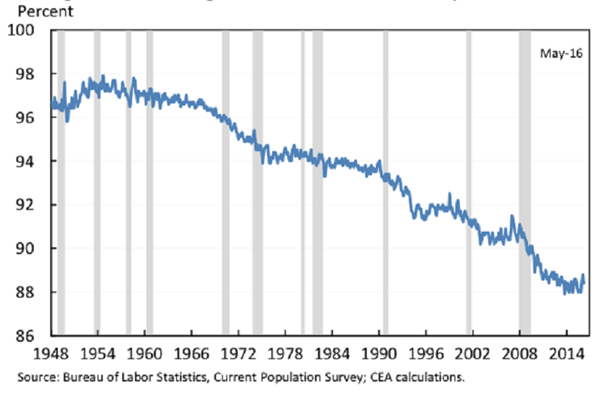

Third, PAMLFPR has been getting worse gradually since about 1960, with no sign of any recent worsening. It is hard to explain why technological unemployment would have started around that time – at least if we limit our explanations to the nature of technology alone. And it doesn’t seem to match the more sudden decline in manufacturing around 2000.

Following this section, he then goes into a section how automation seems to be driving people from middle-skill jobs to lower-skill jobs.

What Scott sees but doesn’t notice the ramifications of, is that the increase in PAMLFPR is a long-term trend as is automation.

Being a discouraged worker requires having looked for a job at some point. But if the long-term trend is there are no jobs, a young man will give up before he starts. He might want a job in some vague sense, the same way you might want a million dollars or a Ferrari, but he knows it’s not going to happen, so he doesn’t try in the first place.

This is where the PAMLFPR’s come from.

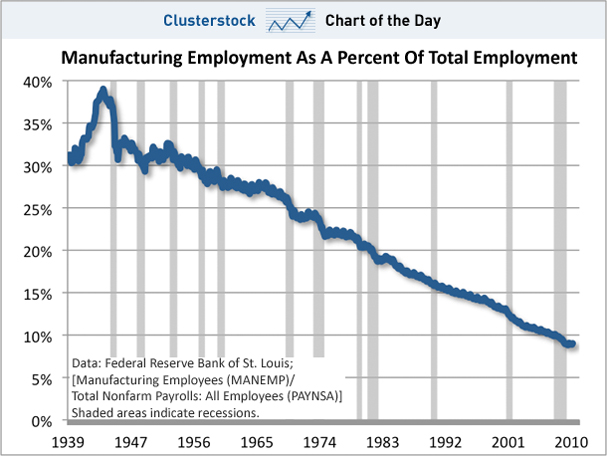

Scott asked why technological unemployment started around 1960, but if we compare the manufacturing employment it begins to decline about 1950 or so (ignoring the WW2 bump). It leads the increase in PAMLFPR’s by about 10 years, which is more or less what you’d expect, given that young men take some time to adapt to new market conditions. (Scott points out: “87% [of manufacturing unemployment] is due to increasing productivity/automation”).

As you can see, with a bit of an expected lead time, manufacturing employment and the increase in PAMLFPR’s (ie. decrease in employed PAM’s) are pretty heavily correlated. Manufacturing employment as a percentage of employment declined from 30% to 10%, while PAM employment declined from about 97% to 88%. A 20-point decline in manufacturing employment is met by a 9-point decline in PAM employment.

This is what you’d expect from technological unemployment, given that many men will find lesser jobs elsewhere, instead of dropping out entirely.

In this long-term trend, many are going to drop out preemptively. They won’t be discouraged, because they never would have been “encouraged” in the first place. Technological employment won’t show up on these charts, because it is long-term, generational, and permanent, while these charts examine “normal” economic processes.

Scott also asks, “Why didn’t previous eras of improving automation result in job loss?” Economists say that past technological advancements increasing productivity had not historically reduced employment. So why is it doing so now?

The answer is simple. Previous technological advances required humans to make them. Agriculture advances: fewer farmers, but farmers become buggy makers. Ford makes the Model T: fewer buggies, but buggy makers becomes car assemblers. Robots are invented: fewer car assemblers, but car assemblers become machine assemblers. But at this stage the pattern changes. Machines start assembling other machines.

Machines assembling machines is a fundamental change in the way the economy works. Other technological advances required human workers to implement them and build the new technologies, but when robots make robots, there is minimal need for humans, the robots are replacing them permanently.

Of course, this is not happening all at once, and that’s why the charts are a decline not straight drop, but this technological shift is fundamentally different and is permanent (barring industrial collapse). What happened in previous eras is irrelevant.

There are other related reasons of “why now?”: prosperity, entertainment, and the decline in marriage and fertility.

We are prosperous enough that practically everybody has their basic needs met. Unless you are mentally ill, a drunkard, or a druggy, you’re almost guaranteed a roof over your head. Our poor people are fat, so no one’s going without food. Entertainment is cheap: for $100 you can get internet, Netflix, and a video game or two each month. In the past a young man had to work or starve; now, with a few roomies, or an indulgent parent or girlfriend, a young man can live very comfortably with nothing more than a small disability cheque and/or the occasional side hustle.

One former discouragement of being unemployed is the boredom of having nothing to do. Now, one $60 video game can provide hundreds of hours of entertainment, $7 gets you Netflix, and $50 internet access provides unlimited entertainment if you don’t mind pirating.

inally, and probably most importantly, men work primarily to take care of their families. It doesn’t take much for a man to provide a comfortable life for himself: a cheap, shared apartment or mother’s basement, tendies and ramen, and an Xbox. That doesn’t cost very much. Men only really need real money if they’re taking care of their family. With the average age of marriage being 30+, declining marriage rates (25% of millenials won’t marry, period), and declining fertility, a significant portion of young men will never have to shoulder family responsibility, and those that do won’t until much later in life. If he’s not supporting a family, he doesn’t really need to be employed.

So, let’s take a look at a low-skilled 22-year-old male looking at his future, here’s what he faces: medium-status jobs are an impossibility, his dad’s job at Ford will replaced by a machine when he’s forcibly retired at 55 and the job is never coming back. He’ll probably never get married; if he gets your girlfriend pregnant, odds are they’ll break-up anyway and she’ll be supported by the welfare state. He could get a job at McDonald’s but half his pay will go to child support, so it doesn’t really seem worth it. If his parents let him stay in their basement and feeds him, the occasional under-the-table job, a small disability cheque, and a few bucks from Patreon for a game review blog or a few Fiverr jobs get you an Xbox and enough games. If they kick him out, he lives at his buddies for some cheap under-the-table rent and maybe he gets the job at McDonald’s or maybe he just does a bit more under-the-table work or starts selling weed. If his buddy kicks him out and things get too bad, he shoots himself, adding to the ever-rising white male suicide rate.

Is this 22-year-old unemployed? No. Is he a discouraged worker? No. Will he ever be a productive member of society? Probably not. Is he suffering? Maybe existentially, but not materially.

If he technologically unemployed? By any reasonable analysis he is. If his father’s job wasn’t going to be replaced by a machine, he’d probably work for Ford, be productive, and get married, but he doesn’t have that option. So, he doesn’t work, but he never shows up in any conventional economic analysis, because he has never worked and never plans to work. People dismiss technological unemployment because they didn’t measure him, but still economists wonder, where did he go?

This is the first stage of the Dire Problem. Technological unemployment is invisible, because none of the standard measures measure it and nobody important (except, maybe, Donald Trump) cares about young working-class men, but it is here nonetheless.